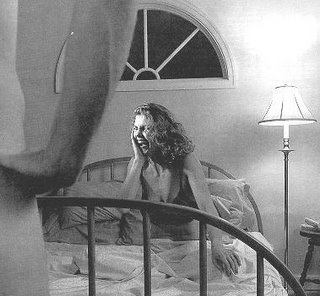

I am lying on a padded table, soaked with sweat, shivering so violently it must appear that I’m having a seizure. I don’t look at myself. My gaze wanders across the ceiling, the lights, the faces darting in and out of my peripheral vision. I am focusing only on the sensations of my body. Someone draws blood from my arm. Normally terrified of needles, there is too much happening around me to give it more thought. “Where is my husband?” I ask. “I want him.” I may just have something to say to him before I die.

“Ms. Valentine, you’re having a heart attack,” a male voice says. I barely glance in his direction. “On a scale of one to ten, with one being the least, and ten being the worst, how is your pain?”

It is not at all what I expect. There is no elephant sitting on my chest. There is no golf ball lodged in my throat. There is only an angry, clenched fist squeezing my heart. It makes me feel incompetent and unworthy of complaining. It's probably not as bad as having a limb severed. I try to rate it fairly. “Six, maybe,” I say. Wondering if I am going to die, I watch for the tunnel that will lead me to the light, and the faces of loved ones who have gone before me, but there is nothing. I surrender my body to the people working on it.

A woman to my right says she is going to cut off my nightgown. Not waiting for my protest, she snips the straps, then gathers the silky fabric from the bottom until it is bunched in her hand above my chest. She begins working her scissors through it. I am naked underneath, and someone covers me with a sheet from the waist down.

Other hands place suction cups on my chest: one on each side below my collarbones, one just above my solar plexus, one below my left breast, another on the right, below where my gall bladder resides. A cuff is fastened around my upper arm. A clamp goes over my finger. It has a glowing red light, and I think ET, phone home.

“Do you have a history of coronary disease?” the man asks.

“My mother.”

“Diabetes?”

“Mother.”

“High blood pressure?”

“I don’t know.”

“Cancer?”

“Not that I know of.”

“Do you smoke?”

“I just quit.”

“When?”

“About thirty minutes ago.”

He has probably heard this joke a thousand times. He doesn’t laugh. He doesn’t even pause. “How much?”

“A pack a day.”

“Do you drink?”

“Occasionally.”

“Have you had any alcohol today?”

“No.”

"Have you taken any drugs?"

"No."

“When did your symptoms begin?”

“About thirty minutes ago.”

“What were the symptoms?”

“I felt weak. Nauseous.”

“Did you vomit?”

“Yes.”

“How many times?”

I look over at him. He is watching my heartbeat on a monitor as he waits for my answer. There were those first few times in the front bathroom. I thought I would feel better. I always feel better after I throw up. I tried to recall what I had eaten and wondered if my husband felt sick, too. It was three or three-thirty in the morning and he had to get up in two hours. He was sleeping soundly, but I felt horrible, and secretly hoped he would come to my aid. I had been in my office on the computer, then gone to the kitchen for something to drink. I crawled into the bedroom and called his name. “Do you feel sick?” I asked.

“No,” he answered. He didn’t ask why I wanted to know.

“I’m sick,” I said. I crawled onto the bed, but didn’t feel better, so I rolled off, lunging toward the master bathroom to keep from tossing my cookies on the floor. I didn’t feel like cleaning up a mess. On my knees, I raised the lid of the toilet and vomited a few more times. Sweat beaded on my skin, drenching me as if I had been standing in a shower. A shower was not a bad idea, I thought. Maybe it would make me feel better. Struggling to reach the faucet handles, I managed to turn one. The blast of cold water did nothing to help. I lay with my face pressed to the cool tile of the shower floor and called my husband again. He must have detected enough panic in my voice that he came. “I’m so sick,” I said. “I need you to call the hospital and tell them my symptoms. See what they say.”

He left and returned with a phone book, sat on the bed, and tried to find a number for the hospital. I felt the squeeze on my heart. “Forget that. Call 911.”

He looked at me like I was crazy.

“I’m telling you, I’m sick! Call 911.”

He stood. “I can get you there faster.”

“Fine.” I didn’t want to waste time arguing about it. “Grab my purse from under my desk. It has my insurance card in it.” He headed for my office, and I began to crawl through the bedroom. From the hall, I watched him search for it. I saw it under my desk, where it lives. “It’s right there!” I shouted.

“Where?”

“Bend over and look. It’s right there under my desk. I’m looking right at it.” He looked and still didn’t see it. I began to get frustrated. “It’s pink and yellow! It has bamboo handles and looks Chinese. It’s right there!” He finally found it, set it on the desk, and began to rummage through it, looking for the card. “Just bring it,” I whined. “I know where it is. I need to go. Now.”

I crawled the rest of the way down the hall and through the living room. He opened the front door, and I crawled across the porch, and down the sidewalk until I reached the driveway where his truck was parked. Managing to stand, I opened the tailgate, and threw myself into the bed.

“What are you doing?” he asked.

“Just get me to the fucking hospital,” I snapped. I braced myself for the bumps in the road and watched treetops and streetlights whiz by. I knew instinctively which stop signs he ran, and exactly where we were by the turns he made. At the hospital, he ran in and reappeared with a wheelchair.

“They said if I can’t get you out of the truck, they don’t know how I expect them to,” he offered by way of explanation. A car pulled up behind us, and I wondered if it was police, but I couldn’t see past the glare of its headlights. I crawled out of the truck and fell into the chair. Once inside, I didn’t have to wait. Someone took control and wheeled me into an inner room, stopping in front of a scale, and told me to hop on.

“I can’t.”

“You have to. We have to know your weight.”

I tumbled from the chair and lay on the scale in a fetal ball. One hundred and thirty-five pounds. I need to diet if I live.

“How many times did you vomit?” the man asks again, bringing me back to the present.

I realize he is the emergency room physician. “Six or seven,” I answer, wishing I could brush my teeth now.

“Do you have a living will or any medical directives?”

Damn. I’ve always meant to do that, but have never gotten around to it.

“Lift your tongue,” a woman says, and I expect a thermometer. “This is nitro glycerin. Let it dissolve.” I have heard of this before. Never in a million years would I expect to have any of it under my own tongue. Suddenly there’s a person on either side of me, inserting IV feeds into each of my arms. A man easily slides a tube the size of a swizzle stick into my right arm, but the woman on my left is having trouble. I scream. She tries again. I curse and look over to see why she’s having such a hard time of it. She says she must have hit a nerve, and wiggles the tube around again to prove it. I think I’m going to get off the table and slap her. A woman standing beside her takes over.

“How is the pain now?” the nitro woman asks.

“Still six.” It hasn’t let up, and now I have a pain in my arm, too. She puts another tiny pill under my tongue.

A man comes to stand at my left. “I have to shave you,” he informs me, but with a reassuring voice, as if he’s waiting for my consent. “They’re going to make an incision in your groin for a catheter.” I know just what he’s talking about. My mother had it done. They snaked a tube up the artery in her leg until they reached her heart. She’d almost died. From the next room, I’d heard the doctor yelling at her, “Stay with me. Stay with me.” I am already neatly trimmed and the shave takes less than ten seconds.. I close my eyes and the dark canvas behind them spins. The tunnel, I think, but no; it’s a snowflake. I want to be cognizant if I leave my body. I’m focused on that. I wait.

“How’s the pain?” nitro nurse asks again.

It’s less, I think. A five. A four, maybe. She puts more nitro under my tongue.

“Let’s get ready to lift,” the doctor directs, and they all surround me. Someone says, “go,” and they lift the sheet under me, just like on TV. I float through the air for a brief moment and land on a gurney. They are off and running. The lights on the ceiling above me speed by like the dotted line on a highway. An elevator door opens and I am wheeled in. A moment later, I am wheeled out. I float again. I see a monitor on my left, nothing more. A cool liquid antiseptic is applied to my groin. I think about how I don’t like the word groin. It sounds nasty. I hear the surgeon’s voice say, “I’ve got two and a half minutes. Let’s go.” I can tell by his accent that he’s from India. I fade to black.

I awaken in a glass room. The nurse’s desk is just outside. The door is open, and I hear activity out there, voices and footsteps. Someone drops a metal object that rings out. In the other direction, I see it’s still dark outside. There are no hospital smells. The bed I’m lying in hums as it shifts slightly, like a wave in a water bed. I’m still tethered to the IV and suction cups. When I move, the top line of the monitor squiggles. I raise my hand a few times when I discover the correlation. An oxygen tube rests beneath my nose. I’m still ET. The blood pressure cuff huffs and puffs and tightens around my arm, then gives a deep sigh. Still adrift in the land of nod, I hear my husband saying that I need my rest and he’ll come back later. I am vaguely aware of the doctor’s presence. He congratulates me for making it to the hospital in time, and explains what he’s done to me, but only a few words stick: massive heart attack, widowmaker, stent. There’s a second blockage in the back of my heart that is unreachable. It is only pumping at 40%. Then he is gone, and I am left alone to contemplate my mortality, and the year from hell that has led me here. Stress is a killer.

***

“How are you feeling?” Two nurses, one male, one female are at my bedside, watching the monitor, checking the EKG wires.

“Fine,” I yawn. Sleeping great until they ran in here. I wonder why they always awaken people who are sick.

“Are you having any pain now?”

I check. I think I feel relatively well for someone in intensive care.

“Your heart stopped,” the man says.

“You set off alarms at the desk,” the woman adds.

“Really? Huh. I was sleeping. I didn’t feel a thing.”

They fuss over me until they’re satisfied I’m still alive. I’m not at all uneasy. It seems it would have been a quick and painless death. Nothing to it. I close my eyes and go back to sleep.

On the third day, the cardiologist brings a medical student with him when he comes to release me from the hospital. He sits on the bed while writing prescriptions for the pills I will need to take the rest of my life, however long that may be. He asks me to recount my symptoms for the student. I realize that until now, I have left out the first symptom, the most important one, I think. The very first thing I recall happening was suddenly being filled with an overwhelming sense of dread, an impending sense of doom. I’d been filled with panic for some reason I hadn’t yet understood. The cardiologist raises his head, and his eyes light with an interest they’ve not had until now, but he says it’s common. I like to think it was an intuitive warning. Lacking a transcendental near death experience, it’s the closest thing to a metaphysical experience I get to take with me.

THIS IS NOT THE TIME TO STOP READING. Symptoms for men and women ARE DIFFERENT. You must know the risk factors and memorize the symptoms of heart attacks for women.

We erroneously believe breast cancer is the number one killer of women, but that’s not true. 433,000 American women will die from cardiovascular disease, followed by cancer (270,000) and chronic lower respiratory disease (67,000).

Thirty-six percent of all women in the U.S. suffer from cardiovascular disease, which includes hypertension, coronary heart disease, and angina. That's 42 million women--more than 1of every 3.

The normal life span is shortened by 15 years after a heart attack.

It is the LEADING CAUSE OF DEATH in the world, for both men and women.

FACTORS THAT PUT WOMEN AT RISK OF HEART ATTACKS:

· You smoke. Period.

· Genetics. One or both parents, or grandparents, or siblings, have heart disease, or died of cardiac arrest.

· High cholesterol, and a diet consisting of too much fat. Almost any fat is too much. If you eat eggs, butter, bacon, sausage, red meat, pork, sweets, or anything else filled with animal fat or unsaturated oil, chances are you have high cholesterol. Yes, that does mean vegetable oil! Switch to safflower oil if you must have it (olive oil is better). And watch the salad dressing. Is it olive or walnut oil? If not, put it down.

· High blood pressure. African Americans, Mexican Americans, Native Americans, Asian Americans, and Hawaiians are at greatest risk. Consuming too much alcohol raises blood pressure. On the other hand, ONE drink a day is good for you.

· You are obese or have diabetes. Seventy-five percent of all people with diabetes die of some form of heart ailment.

· You live a sedentary lifestyle. A dash to the refrigerator during commercials does not constitute exercise.

· You have reached menopause. The estrogen that used to protect your heart isn’t there anymore.

· Stress. In the mind – body connection, heart dis-ease is connected to a feeling of being unloved and unappreciated. Type A personalities and Super Moms are at highest risk. Stress, a byproduct of depression, raises cortisol production, which can cause erratic heartbeats (arrhythmia), raise bad cholesterol, and increase the accumulation of abdominal fat. Stress activates the immune system, which in turn triggers white blood cells to attack bad cholesterol in the arteries. Sounds good, right? No. The consumption of the cholesterol leads to a hardening of the cells, resulting in the formation of deadly plaques.

· You don’t maintain friendships. Female heart attack victims report a low quality of life when it comes to having friends and family to socialize and do things with. Get off the computer once in a while and have lunch (or work out) with a girlfriend. Research confirms that isolation hurts us, and connection heals us. We need people to talk to and spend time with. Friendship and companionship are extremely important to well being. Women with fewer than six regular contacts outside the house have significantly higher rates of blocked coronary arteries, are likely to be obese, have diabetes, high blood pressure, depression, and were two and a half times more likely to die of heart disease-related events than those with an extensive social network. Having just one close friend cuts the risk of mortality by heart disease related events by a third, and the benefit increases the more your circle broadens. Both quality and quantity count.

· Your marriage is less than happy. Studies on marriage, communication, and death show that women who don’t express themselves during disagreements with their husbands are four times more likely to die, compared with women who express themselves freely. A happy marriage cuts the risk of mortality by a third. We mentally replay negative interactions, which in turn activate emotional responses, including depression and hostility, which in turn, increases the risk of heart disease. Marriage is supposed to be a partnership, not a dictatorship.

· Moderate anger is healthy. Hostility is not. A study of eight hundred postmenopausal women found those who were hostile were more than twice as likely to have a heart attack or die from heart problems than those with moderate anger. Expressing moderate anger actually reduces the risk of a heart attack.

· Depression. Heart disease is the world's leading cause of death, and depression feeds it. It wears on our psyche, saps us of the will to look after ourselves, and disrupts our body's biological processes. Serotonin depletion in the brain leads to heart attacks, aortic stenosis, and other malfunctions in the heart. It may be that a depressed person is more likely to make bad lifestyle choices - everything from improper diet to drug and alcohol abuse, to neglecting to take one's blood pressure medications.

About one in five people suffer through a period of major depression in their lifetimes. That number climbs to about one in two among people with heart disease.

Three to five percent of the population is depressed at any given time, but in heart patients, the number rises to eighteen percent.

The risk of heart disease doubles for the depressed, who are four times more likely to die within six months after a heart attack as their non-depressed counterparts.

Depressed patients with newly diagnosed heart disease are twice as likely to have a heart attack or require bypass surgery.

The depressed are four times more likely to have a heart attack within fourteen years of diagnosis.

Depressed men are seventy percent more likely to develop heart disease than non-depressed men. The number was significantly lower for women at twelve percent, but rises to a whopping seventy-eight percent in cases of severe depression.

Despite these findings, cardiologists rarely address depression. Studies show that almost no patients are accurately diagnosed or treated with antidepressants over a seven-month period after a heart attack, despite the fact that patients respond well to anti-depressants, which are safe for them to take. If your doctor refuses to treat your depression before or after a heart disease related event, find a new doctor.

· Jobs of unskilled labor with a lack of autonomy. Working for low pay in jobs considered “unskilled labor,” where job satisfaction is practically nil, and there is no autonomy or decision making, greatly increases heart disease. Chronic job strain after a first heart attack may double the risk of suffering a second one. A job is defined as stressful if it combines high psychological demands such as a heavy workload, intense intellectual activity, or important time constraints, plus little control over decision-making, a lack of autonomy, creativity, or opportunities to use or develop skills. All the usual suspects affect health -- material conditions, smoking, diet, physical activity and so forth, but autonomy and social participation are two other crucial influences on heart disease. The lower the social status, the less autonomy a woman has. A lack of social participation, positive social recognition, and not feeling like a valuable member of society increases the risk of heart disease in spades. These women are also more likely to have fewer friendships and suffer negative relationships, increasing their risks further. Perceiving work as satisfying cuts the risk of a heart attack in half.

· A previous panic attack. Mature women who experience at least one full-blown panic attack have an increased risk of heart attacks and strokes, and an increased risk of death within five years. Having one or more panic attacks is associated with four times the risk of myocardial infarction (the death of heart tissue), three times the risk of having a heart attack or stroke, and nearly twice the risk of death from any cause. The associations remained after controlling for depression, suggesting that panic attacks may be a separate, independent risk factor for cardiovascular events.

· A spiritual path. Reasonably well-done studies on spirituality indicate its importance in our lives for both mental and physical health. Women who search for meaning in their lives by way of religion or spirituality survive loss, cancer, and heart disease better, and have healthier immune chemistry and lower risks of stroke and Alzheimer's disease, than those who do not. People who report that faith is an important part of their lives have higher levels of life satisfaction and emotional well-being.

SYMPTOMS OF HEART ATTACK IN WOMEN

An overwhelming sense of dread. One of the very first symptoms experienced may be a sense of impending death or doom, possibly caused by chemicals in the brain cascading down to the heart. This occurs just moments before the attack.

Sudden weakness. Those of you who are diabetic or hypoglycemic may compare it to the feeling caused by a sudden drop in blood sugar. It feels as if someone has just unplugged your power cord, or you’re a marionette whose strings have been cut.

Nausea. If you think you may have come down with a stomach virus, or may have eaten something bad, watch for other symptoms.

Shortness of breath, now and previously. If someone accuses you of sighing a lot, you may not be breathing well. Your heart may not be pumping enough to carry oxygen to your brain.

Profuse sweating, now and previously. If a little bit of exertion causes you to look like you’ve just stepped out of a shower, get to a doctor. Don’t wait for the attack to sneak up on you.

Inordinate bruising. If you bruise from spraying on your deodorant, tell your doctor. Ask him to check your heart (this can also be a symptom of leukemia). This is not ordinarily listed among the symptoms, but something I noticed in myself. Since the attack, I no longer bruise beyond what's occasionally normal.

Pain in the chest, arm, or jaw. Pain is the body’s way of telling the brain that something is wrong. Listen. Now is not the time to “walk it off.” Don’t lie on the bed and think it will go away in a few minutes. You may never get up again. Don’t say, “It’s nothing.” It’s something, and it’s something deadly.

HERE’S WHAT TO DO IF YOU THINK YOU MAY BE HAVING A HEART ATTACK:

If you are alone, call 911 immediately. If possible, get to the door to unlock it so that paramedics can enter. They can’t save you if they can’t get to you. If you’re not alone, summon someone and instruct them to call 911. And if you’re the person responding, don’t argue with the patient. You can’t know what their body is doing, or telling them. Make the damned call.

Do not allow a friend or family member to drive you to the hospital except as a last resort. Chances are they cannot save your life if you die in route. They will also go to the nearest hospital, but that hospital may not have the cath lab or other facilities needed to save you. Paramedics in an ambulance, on the other hand, can begin treatment immediately, communicate with doctors, take you to the proper facility, and resuscitate you if you die.

Never attempt to drive yourself to the hospital. You’ll not only endanger yourself, but others.

Do not lie down, thinking it will go away in a few minutes. You may go away in a few minutes, and you will never be coming back. Women are particularly guilty of blowing it off. Mothers are so used to putting everyone ahead of themselves, and of being indispensable, they convince themselves and others, “It’s nothing; I’ll be okay in a few minutes.” You will not be. You are not giving the event the respect it deserves. You are not humbling yourself to the facts. HEART DISEASE IS THE NUMBER 1 KILLER IN THE WORLD. Do you really believe it can’t happen to you?

Please, go back and read the risk factors and symptoms again and again if necessary, until you know them by heart.

* * *

As her date removed his pants, Sheila suddenly recalled a hilarious radio spot she'd heard that morning. Later, when pressed, she'd admit the timing was unfortunate.